This article is about the franchise as a whole. For the character, see Popeye. For other meanings, see Popeye (disambiguation).

Popeye the Sailor was created by E. C. Segar as a supporting character in the daily King Features comic strip Thimble Theatre, appearing on January 17, 1929. The character has since continued to appear in comics and animated cartoons, in the cinema as well as on television. Popeye also became the strip's title in later years.

Even though Segar's Thimble Theatre strip was in its 10th year when Popeye made his debut in 1929, the sailor quickly became the main focus of the strip and Thimble Theatre became one of King Features's most popular properties during the 1930s. Thimble Theatre was continued after Segar's death in 1938 by several writers and artists, most notably Segar's assistant Bud Sagendorf. The strip, now titled Popeye, continues to appear in first-run installments in its Sunday edition, written and drawn by Hy Eisman. The daily strips are reprints of old Sagendorf stories.

In 1933, Max and Dave Fleischer's Fleischer Studios adapted the Thimble Theatre characters into a series of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoon shorts for Paramount Pictures. These cartoons proved to be among the most popular of the 1930s, and the Fleischers — and later Paramount's own Famous Studios — continued production through 1957. These cartoon shorts are now owned by WarnerMedia, a division of AT&T, and distributed by sister company Warner Bros. Entertainment.

Over the years, Popeye has also appeared in comic books, television cartoons, arcade and video games, hundreds of advertisements and peripheral products, and a 1980 live-action film directed by Robert Altman starring comedian Robin Williams as Popeye.

Fictional character and story[]

- Main article: Popeye

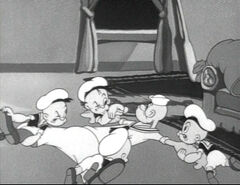

Differences in Popeye's story and characterization show up depending upon which medium he is presented in. While Swee'Pea is definitively the ward of Popeye in the comic strips, he is often depicted as belonging to Olive Oyl in cartoons. The cartoons also occasionally feature family members of Popeye that have never appeared in the strip, notably his look-alike nephews Pipeye, Peepeye, Poopeye, and Pupeye.

Even though there is no absolute sense of continuity in the stories, certain plot and presentation elements remain mostly constant, including purposeful contradictions in Popeye's capabilities. Though at times he seems bereft of manners or uneducated, Popeye is often depicted as capable of coming up with solutions to problems that (to the police, or, most importantly, the scientific community) seem insurmountable. Popeye has, alternatively, displayed Sherlock Holmes-like investigative prowess (determining for instance that his beloved Olive was abducted by estimating the depth of the villains' footprints in the sand), scientific ingenuity (as his construction, within a few hours, of a "spinach-drive" spaceship), or oversimplified (yet successful) diplomatic argumentation (by presenting to diplomatic conferences his own existence --- and superhuman strength --- as the only true guarantee of world peace).

Popeye's vastly versatile exploits are deemed even more amusing by a few standard plot elements. One is the love triangle between Popeye, Olive, and Bluto, and the latter's endless machinations to claim Olive at Popeye's expense. Another is his (near-saintly) perseverance to overcome any obstacle to please Olive – who, quite often, renounces Popeye for Bluto's dime-store advances. She is the only character Popeye will permit to give him a thumping. Finally, in terms of the endless array of villain plots, Popeye mostly comes to the truth by "accidentally" sneaking up on the villains, the moment they are bragging about their schemes' ingenuity, thus revealing everything to an enraged Popeye, who uses his "fisks" in the name of justice.

Thimble Theatre and Popeye comic strips[]

- Main article: List of Thimble Theatre storylines

Segar's Thimble Theatre debuted in the New York Journal on December 19, 1919. The paper's owner, William Randolph Hearst, also owned King Features Syndicate, which syndicated the strip. Thimble Theatre was intended as a replacement for Midget Movies by Ed Wheelan (Wheelan having recently resigned from King Features). While initially failing to attract a large audience, the strip nonetheless increasingly accumulated a modest following as the 1920s continued. At the end of its first decade, the strip resultantly appeared in over a dozen newspapers and had acquired a corresponding Sunday strip (which had debuted on January 25, 1925 within the Hearst-owned New York American paper).

Thimble Theatre's first main characters were the lanky, long-nosed slacker Harold Hamgravy (rapidly shortened to simply "Ham Gravy") and his scrappy, headstrong girlfriend Olive Oyl. In its earliest weeks, the strip featured the duo, alongside a rotating cast of primarily one-shot characters, acting out various stories and scenarios in a parodic theatrical style, hence the strip's name. As its first year progressed, however, numerous elements of this premise would be relinquished (including the recurring character Willie Wormwood, introduced as a parody of melodrama villainy), soon rendering the strip a series of episodic comic anecdotes depicting the daily life and dysfunctional romantic exploits of Ham Gravy and Olive Oyl. It could be classified as a gag-a-day comic during this period. In mid-1922, Segar began to increasingly engage in lengthier (often months-long) storylines; by the end of the following year, the strip had effectively transitioned fully into a comedy-adventure style focalizing Ham, Olive, and Olive's ambitious-but-myopic diminutive brother Castor Oyl, initially a minor character yet arguably the protagonist of the strip by 1924. Castor and Olive's parents Cole and Nana Oyl also made frequent appearances beginning in the mid-1920s. By the late 1920s, the strip had likewise acquired a number of notable characters beyond the sphere of Ham Gravy and the Oyl family, including Castor Oyl's wife Cylinda (to whom he was married from 1926 to 1928), her wealthy, misanthropic father Mr. Lotts and Castor's fighting cockerel Blizzard, all of whom had exited the strip by the close of 1928 (although Cylinda would eventually martially reunite with Castor under Randy Milholland's authorship almost a century later).

Popeye first appeared in the strip on January 17, 1929, as a minor character. He was initially hired by Castor Oyl and Ham Gravy to crew a ship for a voyage to Dice Island, the location of a casino owned by the crooked gambler Fadewell. Castor intended to break the bank at the casino using the unbeatable good luck conferred by stroking the hairs on the head of Bernice the Whiffle Hen. Weeks later, on the trip back, Popeye was shot many times by Jack Snork, an undercover stooge of Fadewell's, but survived by rubbing Bernice's head. After the adventure, Popeye left the strip, but, owing to reader reaction, he was brought back after an absence of only five weeks.

Ultimately, the Popeye character became so popular that he was given a larger role by the following year, and the strip was taken up by many more newspapers as a result. Initial strips presented Olive as being less than impressed with Popeye, but she eventually left Ham to become Popeye's girlfriend in March 1930, precipitating Ham's exit as a regular weeks later. Over the years, however, she has often displayed a fickle attitude towards the sailor. Initially, Castor Oyl continued to come up with get-rich-quick schemes and enlisted Popeye in his misadventures. By the end of 1931, however, he settled down as a detective and later on bought a ranch out west. Castor's appearances have resultantly become sparser over time. As Castor faded from the strip, J. Wellington Wimpy, a soft-spoken and eloquent yet cowardly hamburger-loving moocher who would "gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today" was introduced into the Sunday strip, in which he became a fixture by late 1932. After first appearing in the daily strip in March 1933, Wimpy became a full-time major character alongside Popeye and Olive.

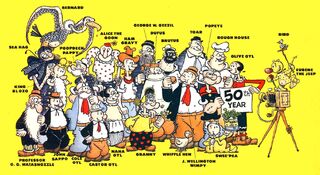

In July 1933, Popeye received a foundling baby in the mail whom he adopted and named Swee'Pea. Other regular characters introduced into the strip following its retool in 1930 were George W. Geezil, an irascible cobbler who spoke in a heavily affected accent and habitually attempted to murder or wish death upon Wimpy; Rough-House, the temperamental owner of a budget diner who served as a long-suffering foil to Wimpy; Eugene the Jeep, a yellow, vaguely doglike animal from Africa with magical powers; the Sea Hag, a terrible pirate and the last witch on Earth; Alice the Goon, a bizarre, lanky, oscilloscope-voiced creature who entered the strip as the Sea Hag's henchwoman and continued as Swee'Pea's babysitter; the hapless, perpetually anxious King Blozo; Blozo's unintelligent lackey Oscar; Popeye's lecherous, superannuated father Poopdeck Pappy; and Toar, an ageless, dim-witted caveman.

Segar's strip was quite different from the theatrical cartoons that followed. The stories were more complex (often spanning months or even years), with a heavier emphasis on verbal comedy and many characters that never appeared in the cartoons (among them King Blozo, Toar, and Rough-House). Spinach usage, a trait introduced in June 1931, was comparatively infrequent, and Bluto appeared in only one story arc. Segar signed some of his early Popeye comic strips with a cigar, his last name being a homophone of "cigar" (pronounced SEE-gar). Comics historian Brian Walker stated: "Segar offered up a masterful blend of comedy, fantasy, satire and suspense in Thimble Theatre Starring Popeye".

Owing to Popeye's increasingly high profile, Thimble Theatre became one of King Features' most popular strips during the 1930s. A poll of adult comic strip readers in the April 1937 issue of Fortune magazine voted Popeye their second-favorite comic strip (after Little Orphan Annie). By 1938, Thimble Theatre was running in 500 newspapers, and over 600 licensed "Popeye" products were on sale. The success of the strip meant Segar was earning $100,000 a year at the time of his death. The strip continued after Segar's death in 1938 under a succession of artists and writers. Following an eventual name change to Popeye in the 1970s and the cancellation of the daily strip in 1992 (in favor of reprints), the comic, now solely a Sunday strip, remains one of the longest-running strips in syndication today.

Artists after Segar[]

After Segar's death in 1938, many different artists were hired to draw the strip. Tom Sims, the son of a Coosa River channel-boat captain, continued writing Thimble Theatre strips. Doc Winner and Bela Zaboly successively handled the artwork during Sims's run. Eventually, Ralph Stein stepped in to write the strip until the series was taken over by Bud Sagendorf in 1959.

Sagendorf wrote and drew the daily strip until 1986, and continued to write and draw the Sunday strip until his death in 1994. Sagendorf, who had been Segar's assistant, made a definite effort to retain much of Segar's classic style, although his art is instantly discernible. Sagendorf continued to use many obscure characters from the Segar years, especially O. G. Wotasnozzle and King Blozo. Sagendorf's new characters, such as the Thung, also had a very Segar-like quality. What set Sagendorf apart from Segar more than anything else was his sense of pacing. Where plotlines moved very quickly with Segar, it would sometimes take an entire week of Sagendorf's daily strips for the plot to be advanced even a small amount.

From 1986 to 1992, the daily strip was written and drawn by Bobby London, who, after some controversy, was fired from the strip for a story that could be taken to satirize abortion. London's strips put Popeye and his friends in updated situations, but kept the spirit of Segar's original. One classic storyline, titled "The Return of Bluto", showed the sailor battling every version of the bearded bully from the comic strip, comic books, and animated films. The daily strip began featuring reruns of Sagendorf's strips after London was fired and continues to do so today.

Hy Eisman took over the Sunday strip in 1994 after Sagendorf's death. The Sunday edition of the comic strip is currently drawn by Randy Milholland, following Eisman's retirement in 2022.

On January 1, 2009, 70 years since the death of his creator, Segar's character of Popeye (though not the various films, television series, theme music and other media based on him) became public domain in most countries, but remains under copyright in the United States. Because Segar was an employee of King Features Syndicate when he created the Popeye character for the company's Thimble Theatre strip, Popeye is treated as a work for hire under U.S. copyright law. Works for hire are protected for 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter. Since Popeye made his first appearance in January 1929, and all U.S. copyrights expire on December 31 of the year that the term ends, Popeye will not enter the public domain in the U.S. until January 1, 2025 (assuming that no further term extensions are passed into law in the interim).

Comic books[]

There have been a number of Popeye comic books, from Dell, Gold Key Comics, Charlton Comics and others, originally written and illustrated by Bud Sagendorf. In the Dell comics, Popeye became something of a crimefighter, thwarting evil organizations and Bluto's criminal activities. New villains included the Misermite dwarfs.

Popeye also appeared in the British TV Comic series, a News of the World publication, becoming the cover story in 1960 with stories written and drawn by "Chick" Henderson.

A variety of artists have created Popeye comic book stories since then; for example, George Wildman drew Popeye stories for Charlton Comics from 1969 until the late 1970s. The Gold Key series was illustrated by Wildman and scripted by Bill Pearson, with some issues written by Nick Cuti.

In 1987, Ocean Comics released its first Popeye Special written by Ron Fortier with art by Ben Dunn. The story presented Popeye's origin story and tried to tell more of a lighthearted adventure story as opposed to using typical comic strip style humor. The story also featured a more realistic art style and was edited by Bill Pearson, who also lettered and inked the story as well as the front cover. A second issue, by the same creative team, followed in 1988. The second issue introduced the idea that Bluto and Brutus were actually twin brothers and not the same person. In 1999, to celebrate Popeye's 70th anniversary, Ocean Comics revisited the franchise with a one-shot comic book, entitled The Wedding of Popeye & Olive, written by Peter David. The comic book brought together a large portion of the casts of both the comic strip and the animated shorts, and Popeye and Olive Oyl were finally wed after decades of courtship. However, this marriage has not been reflected in other media since the comic was published.

In 1989, a special series of short Popeye comic books were included in specially marked boxes of Instant Quaker Oatmeal, and Popeye also appeared in television commercials for Quaker Oatmeal which featured a parrot delivering the tagline "Popeye wants a Quaker!" The plots were similar to those of the films: Popeye loses either Olive Oyl or Swee'Pea to a muscle-bound antagonist, eats something invigorating, and proceeds to save the day. In this case, however, the invigorating elixir was not his usual spinach, but rather one of four flavors of Quaker Oatmeal. (A different flavor was showcased with each mini-comic.) The comics ended with the sailor saying, "I'm Popeye the Quaker Man!", which offended members of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers. Members of this religious group (which has no connection to the cereal company) are pacifists and do not believe in using violence to resolve conflicts. For Popeye to call himself a "Quaker man" after beating up someone was offensive to the Quakers and considered a misrepresentation of their faith and religious beliefs. After a brief protest, the Quaker Oatmeal Company pulled the comic books and commercials in 1990, and the promotional campaign remains little-known.

In 2012, writer Roger Langridge and cartoonist Bruce Ozella teamed to revive the spirit of Segar in IDW Publishing's Popeye comic book series, with issue #1 by Ozella and issues #2 and #3 by Ken Wheaton and Tom Neely. Critic PS Hayes reviewed:

- Langridge writes a story with a lot of dialogue (compared to your average comic book) and it’s all necessary, funny, and entertaining. Bruce Ozella draws the perfect Popeye. Not only Popeye, but Popeye’s whole world. Everything looks like it should, cartoony and goofy. Plus, he brings an unusual amount of detail to something that doesn’t really need it. You’ll swear that you’re looking at an old Whitman Comics issue of Popeye, only it’s better. Ozella is a great storyteller and even though the issue is jam packed with dialog, the panels never look cramped at all.[1]

Animated cartoons[]

- Main article: List of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoons (Fleischer Studios)

- Main article: List of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoons (Famous Studios)

Popeye, preparing to eat his spinach, in Fleischer Studios' Little Swee'Pea (1936)

In November 1932, King Features signed an agreement with Fleischer Studios to have Popeye and the other Thimble Theatre characters begin appearing in a series of animated cartoons. The first cartoon in the series was released in 1933, and Popeye cartoons, released by Paramount Pictures, would remain a staple of Paramount's release schedule for nearly 25 years. Many of the Thimble Theatre characters, including Wimpy, Poopdeck Pappy, and Eugene the Jeep eventually made appearances in the Paramount cartoons, though appearances by Olive Oyl's extended family and Ham Gravy were notably absent. Thanks to the animated short series, Popeye became even more of a sensation than he had been in comic strips, and by 1938, polls showed that the sailor was Hollywood's most popular cartoon character.[2]

In every Popeye cartoon, the sailor is invariably put into what seems like a hopeless situation, upon which (usually after a beating), a can of spinach which he apparently regularly carries with him falls out from inside his shirt. Popeye immediately pops the can open and gulp the entire contents of it into his mouth, or sometimes sucks in the spinach through his corncob pipe. Upon swallowing the spinach, Popeye's physical strength immediately becomes almost superhuman, and he is easily able to save the day (and very often rescue Olive Oyl from a dire situation).

In May 1941, Paramount Pictures assumed ownership of Fleischer Studios, fired the Fleischers and began reorganizing the studio, which they renamed Famous Studios. The early Famous-era shorts were often World War II-themed, featuring Popeye fighting Nazis and Japanese soldiers, most notably the 1942 short You're a Sap, Mr. Jap. In late 1943, the Popeye series was moved to Technicolor production, beginning with Her Honor the Mare. Famous / Paramount continued producing the Popeye series until 1957, with Spooky Swabs being the last of the 125 Famous shorts in the series. Paramount then sold the Popeye film catalog to Associated Artists Productions, which was bought out by United Artists in 1958 and later merged with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which was itself purchased by Turner Entertainment in 1986. Turner sold off the production end of MGM / UA shortly after, but retained the film catalog, giving it the rights to the theatrical Popeye library.

The black-and-white Popeye shorts were shipped to South Korea in 1985, where artists retraced them into color. The retraced shorts were syndicated in 1987 on a barter basis, and remained available until the early 1990s. Turner merged with Time Warner in 1996 and Warner Bros. (through its Turner subsidiary) therefore currently controls the rights to the Popeye shorts.

In 2001, the Cartoon Network, under the supervision of animation historian Jerry Beck, created a new incarnation of The Popeye Show. The show aired the Fleischer and Famous Studios Popeye shorts in versions approximating their original theatrical releases by editing copies of the original opening and closing credits (taken or recreated from various sources) onto the beginnings and ends of each cartoon, or in some cases, in their complete, uncut original theatrical versions direct from such prints that originally contained the front-and-end Paramount credits. The series aired 135 Popeye shorts over 45 episodes, until March 2004. The Popeye Show continued to air on Cartoon Network's spin-off network Boomerang.

While many of the Paramount Popeye cartoons remained unavailable on video, a handful of those cartoons had fallen into public domain and were found on numerous low budget VHS tapes and later DVDs. When Turner Entertainment acquired the cartoons in 1986, a long and laborious legal struggle with King Features kept the majority of the original Popeye shorts from official video releases for more than 20 years. King Features instead opted to release a DVD boxed set of the 1960s made-for-television Popeye the Sailor cartoons, which it retained the rights to, in 2004. In the meantime, home video rights to the Associated Artists Productions library were transferred from CBS / Fox Video to MGM / UA Home Video in 1986, and eventually to Warner Home Video in 1999.

In 2006, Warner Home Video announced it would release all of the Popeye cartoons produced for theatrical release between 1933 and 1957 on DVD, restored and uncut. The first of Warner's Popeye DVD sets, covering the cartoons released from 1933 until early 1938, was released on July 31, 2007.

In 1960, King Features Syndicate commissioned a new series of cartoons entitled Popeye the Sailor, but this time for television syndication. The artwork was streamlined and simplified for the television budgets and 220 cartoons were produced in only two years, with the first set of them premiering in the autumn of 1960, and the last of them debuting during the 1961–1962 television season. For these cartoons, Bluto's name was changed to "Brutus," as King Features believed at the time that Paramount owned the rights to "Bluto." On September 9, 1978, an hour-long animated series produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, The All-New Popeye Hour, debuted on the CBS Saturday morning lineup. It ran until September 1981, when it was cut to a half-hour and retitled The Popeye and Olive Show. It was removed from the CBS lineup in September 1983. Popeye briefly returned to CBS in 1987 for Popeye and Son, another Hanna-Barbera series, which lasted for one season.

In 2004, Lions Gate Entertainment produced a computer-animated television special, Popeye's Voyage: The Quest for Pappy, which was made to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Popeye. Billy West performed the voice of Popeye; after the first day of recording, his throat was so sore he had to return to his hotel room and drink honey. The uncut version was released on DVD on November 9, 2004; and was aired in a re-edited version on Fox on December 17, 2004 and again on December 30, 2005. Its style was influenced by the 1930s Fleischer cartoons, and featured Swee'Pea, Wimpy, Bluto (who is Popeye's friend in this version), Olive Oyl, Poopdeck Pappy and the Sea Hag as its characters. On November 6, 2007, Lionsgate Entertainment re-released Popeye’s Voyage on DVD with redesigned cover art.

Theme song[]

Popeye's theme song "I'm Popeye the Sailor Man," composed by Sammy Lerner in 1933 for Fleischer's first Popeye the Sailor cartoon,[3] has become forever associated with the sailor. As one cartoon historian has observed, Popeye's theme song itself was inspired by two lines of the tune "Oh, Better Far to Live and Die," sung by the Pirate King and chorus in Act I of Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta The Pirates of Penzance: "For I am a Pirate King! (You are! Hoorah for the Pirate King!)" The tune behind those two lines is similar to the "Popeye" song, except for the high note on the first "King". "The Sailor's Hornpipe" has often been used as an introduction to Popeye's theme song.

A cover of the theme song, performed by Face To Face is included on the 1995 tribute album Saturday Morning: Cartoons' Greatest Hits, produced by Ralph Sall for MCA Records.

Other media[]

- Main article: Media

The success of Popeye as a comic-strip and animated character has led to appearances in many other forms. For more than 20 years, Stephen DeStefano has been the artist drawing Popeye for King Features licensing.[4]

Radio[]

Popeye was adapted to radio in several series broadcast over three different networks by two sponsors from 1935 to 1938. Popeye and most of the major supporting characters were first featured in a thrice-weekly 15-minute radio program, Popeye the Sailor, which starred Detmar Poppen as Popeye along with most of the major supporting characters—Olive Oyl (Olive Lamoy), Wimpy (Charles Lawrence), Bluto (Jackson Beck) and Swee'Pea (Mae Questel). In the first episode, Popeye adopted Sonny (Jimmy Donnelly), a character later known as Matey the Newsboy. This program was broadcast Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday nights at 7:15pm. September 10, 1935 through March 28, 1936 on the NBC Red Network (87 episodes), initially sponsored by Wheatena, a whole-wheat breakfast cereal, which would routinely replace the spinach references. Music was provided by Victor Irwin's Cartoonland Band. Announcer Kelvin Keech sang (to composer Lerner's "Popeye" theme) "Wheatena is his diet / He asks you to try it / With Popeye the sailor man." Wheatena paid King Features Syndicate $1,200 per week.

The show was next broadcast Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from 7:15 to 7:30pm on WABC and ran from August 31, 1936 to February 26, 1937 (78 episodes). Floyd Buckley played Popeye, and Miriam Wolfe portrayed both Olive Oyl and the Sea Hag. Once again, reference to spinach was conspicuously absent. Instead, Popeye sang, "Wheatena's me diet / I ax ya to try it / I'm Popeye the Sailor Man".[5] The third series was sponsored by the maker of Popsicle three nights a week for 15 minutes at 6:15 pm on CBS from May 2, 1938 through July 29, 1938.

Of the three series, only 20 of the 204 episodes are still known to exist.

Films[]

- Popeye (1980)

- Main article: Popeye (live-action film)

Director Robert Altman used the character in Popeye, a 1980 live-action musical feature film starring Robin Williams as Popeye (his first movie role), Paul Smith as Bluto and Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl, with songs by Harry Nilsson. The script was by Jules Feiffer, who adapted the 1971 Nostalgia Press book of 1936 strips for his screenplay, thus retaining many of the characters created by Segar. A co-production of Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, the movie was filmed almost entirely on Malta, in the village of Mellieħa on the northwest coast of the island. The set is now a tourist attraction called Popeye Village. The U.S. box office earnings were double the film's budget, making it somewhat of a success.

- Upcoming film

- Main article: Popeye (animated film)

In March 2010, it was reported that Sony Pictures Animation was developing a 3-D computer-animated Popeye film, with Avi Arad producing it.[6] In November 2011, Sony Pictures Animation announced that Jay Scherick and David Ronn, the writers of the Smurfs film, would be writing the screenplay.[7]

Video and pinball games[]

- Nintendo created a widescreen Game & Watch called Popeye in 1981. The handheld game featured Popeye on a boat, and the aim was to catch bottles, pineapples and spinach cans thrown by Olive Oyl while trying to avoid Bluto's boat. If Bluto hit Popeye on the head with his mallet, or Popeye failed to catch an object three times, the game would end.

- The Nintendo arcade game Donkey Kong was originally conceived as a Popeye video game by Shigeru Miyamoto, but due to several factors, this idea was scrapped and the game was developed with original characters.

- Following Donkey Kong's great success, King Features licensed the characters to Nintendo to create an actual Popeye arcade game in 1982. It was later ported to the Commodore 64 home computer as well as various home game consoles: Intellivision, Atari 2600, ColecoVision, Famicom / NES and Odyssey2. The goal was to avoid Brutus and the Sea Hag while collecting items produced by Olive Oyl such as hearts, musical notes, or the letters in the word "help" (depending on the level). Hitting a can of spinach gave Popeye a brief chance to strike back at Brutus. Other characters such as Wimpy and Swee' Pea appeared in the game but did not greatly affect gameplay. The game is playable on the MAME game emulator computer program for PC. A board game based on the video game was released by Parker Brothers.

- A table top Game & Watch style game was also released by Nintendo in 1983, which featured Popeye trying to rescue Olive while engaging in fisticuffs with Bluto.

- Nintendo created another Popeye game for the Famicom, Popeye no Eigo Asobi, in 1983. This was an educational game designed to teach Japanese children English words.

- Two Popeye games published by Sigma Enterprises were spawned for Nintendo's handheld Game Boy: Popeye, which was released exclusively in Japan in 1990, and Popeye 2 in 1991. Popeye 2 was also released in North America (1993) and Europe (1994) by Activision.

- In 1994, Technos Japan released Popeye: Beach Volley Ball for the Game Gear, and Popeye: Volume of the Malicious Witch Seahag (Popeye: Ijiwaru Majo Seahag no Maki) for the Japanese Super Nintendo (known as the Super Famicom). A side-scrolling adventure game that was mixed with a board game, the game never saw US release. It featured many characters from the Thimble Theatre series as well. In the game, Popeye had to recover magical hearts scattered across the level to restore his frozen friends as part of a spell cast upon them by the Sea Hag in order to get revenge on Popeye.

- Midway (under the "Bally" label) released Popeye Saves the Earth, a SuperPin pinball game, in 1994.

- In 2003, Nova Productions released a strength tester called Popeye Strength Tester.

- In 2005, Namco released a Game Boy Advance video game called Popeye: Rush for Spinach.

- Released in June 2007, the video game The Darkness featured televisions that played full-length films and television series that had expired copyrights. Most of the cartoons viewable on the "Toon TV" channel are Famous Studios Popeye shorts.

- In fall 2007, Namco Networks released the original Nintendo Popeye arcade game for mobile phones with new features including enhanced graphics and new levels.

Marketing, tie-ins, and endorsements[]

From early on, Popeye was heavily merchandised. Everything from soap to razor blades to spinach was available with Popeye's likeness on it. Most of these items are rare and sought-after by collectors, but some merchandise is still being produced.

- Games and toys

- Mezco Toyz makes classic-style Popeye action figures in two sizes.

- KellyToys produces plush stuffed Popeye characters.

- Restaurants

- Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits, a fast food restaurant chain, is not named after Popeye the sailor but after the character "Popeye" Doyle from the 1971 film The French Connection, who was in turn named after real police detective Eddie Egan, who was called "Pop Eye" because of his keen observational skills. The restaurant chain would later obtain a license for use of the cartoon character and advertise the name as Popeye's after Popeye the sailor, causing some confusion as to the source of the name. Popeyes Chicken and Biscuits locations in Puerto Rico made extensive use of Popeye the Sailor and associated characters.[8]

- Wimpy's name was borrowed for the Wimpy Bar restaurant chain, one of the first international fast food restaurants featuring hamburgers, which they call "Wimpy Burgers."

- Retail foods and beverages

- Allen Canning Company produces its own line of spinach, called "Popeye Spinach", in various canned varieties. Popeye serves as the mascot on the label.

- In 1961, Buitoni Pasta marketed Popeye-shaped spinach macaroni.

- Popeye appeared in a 1979 Dr Pepper commercial during the "Be a Pepper" campaign (possibly as a tie-in for the movie, going so far as to modify his traditional catchphrase to "I'm Popeye the Pepper-man").

- In 1989, Popeye endorsed Instant Quaker Oatmeal, citing it as a better food than spinach to provide strength. The commercials had the tagline "Can the spinach, I wants me Quaker Oatmeal!"

- In 2001, Popeye (along with Bluto, Olive, and twin Wimpys) appeared in a television commercial for Minute Maid Orange Juice. The commercial, produced by Leo Burnett Co., showed Popeye and Bluto as friends (and neglecting Olive Oyl) due to their having had Minute Maid Orange Juice that morning. The ad agency's intention was to show that even the notable enemies would be in a good mood after their juice, but some, including Robert Knight of the Culture and Family Institute, felt the commercial's intent was to portray the pair in a homosexual romantic relationship—an allegation that Minute Maid denies. Knight was interviewed by Stephen Colbert on Comedy Central's The Daily Show about this issue.

- World Candies Inc. produced Popeye-branded "candy cigarettes", which were small sugar sticks with red dye at the end to simulate a flame. They were sold in a small box, similar to a cigarette pack. The company still produces the item, but has since changed the name to "Popeye Candy Sticks" and has ceased putting the red dye at the end.

- Sports

- Starting in 1940, Popeye became the mascot of the Flamengo (Rio de Janeiro – Brazil), the most popular soccer team with almost 50 million fans around the world. The mascot of the soccer club is currently a cartoon vulture.[9]

- Other

- In 1979, salsa singer Adalberto Santiago released Adalberto Featuring Popeye El Marino. Fania Records JM 536.

- During the 1960s, Popeye appeared in advertising for Crown gasoline.

- In 1987, Stabur Graphics commissioned artist Will Elder to paint "Popeye's Wedding" as oil on masonite. Released was a stamped, numbered and signed Limited Edition lithograph, edition size of 395. The lithograph shows Popeye and Olive in front of the preacher (Popeye slipping a lifesaver-ring onto Olive's finger) along with Nana Oyl, Alice the Goon, Swee'Pea (cradled in Popeye's free arm), Wimpy, Granny, Eugene the Jeep and Brutus (holding a large cauldron of steaming, cooked rice). Twenty-one other characters watch from the pews. The litho is titled "Wit Dis Lifesaver, I Dee Wed!" and is pictured on page 83 of the book "Chicken Fat" by Will Elder (Fantagraphics, 2006).

- In 1990, Popeye appeared in an advertisement warning of the harmful effects of coastal pollution. Bluto is laughing as he carelessly dumps garbage over the side of his boat, to which Olive reacts in horror as seagulls and other sea creatures are caught in six-pack ring holders. Popeye punches out Bluto and cleans up his garbage; however, when some more plastic garbage sails by Popeye's boat, he says "I can't do it all meself, you know!"

- In 1995, the Popeye comic strip was one of 20 included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative U.S. postage stamps.

- From 1996 to 1999, the Darien Lake theme park in Western New York operated a "Popeye's Seaport" in the park. It was rebranded as "Looney Tunes Seaport" after Darien Lake came under the Six Flags banner.

- In 2005, King Features Syndicate introduced the Baby Popeye line of children's products.

- In 2006, King Features produced a radio spot and an industrial for the United States Power Squadrons featuring Robyn Gryphe as Olive and Allen Enlow as Popeye.

- In October 2007, to coincide with the launch of the Popeye mobile game, Namco Networks and Sprint launched a Popeye the Sailorman sweepstakes offering the authorized edition four-disc Popeye the Sailor: 1933–1938 Vol. 1 DVD set as grand prize.

- In Universal's Islands of Adventure, there is a river rafting water ride, Popeye & Bluto's Bilge-Rat Barges, themed after Popeye the Sailor saving Olive Oyl from Bluto.

- In 2011, alternative rock band Wilco released the song "Dawned On Me," whose animated video stars Popeye as he appeared in old Fleischer Studios cartoons.

Cultural origins and impact[]

- Main article: List of Popeye references in popular culture

Local folklore in Chester, Illinois, Segar's hometown, claims that Popeye is based on Frank "Rocky" Fiegel, a man who was handy with his fists.[10] Fiegel was born on January 27, 1868. He lived as a bachelor his entire life. It was said that later Segar sent checks to Fiegel in the 1930s. Fiegel died on March 24, 1947 at the age of 79.

Culturally,[11] many consider Popeye a precursor to the superheroes who would eventually come to dominate the world of comic books.[12] Some observers of popular culture point out that the fundamental character of Popeye, paralleling that of another 1930s icon, Superman, is very close to the traditional view of how the U.S. sees itself as a nation: possessing uncompromising moral standards and resorting to force when threatened, or when he "can't stands no more" bad behavior from an antagonist. This theory is directly reinforced in certain cartoons, when Popeye defeats his foe while a US patriotic song, usually either "Stars and Stripes Forever," "Yankee Doodle," or "Columbia, Gem of the Ocean", plays on the soundtrack. One of Popeye's catchphrases is "I yam what I yam, and that's all what I yam," which may be seen as an expression of individualism.

Such has been Popeye's cultural impact that the medical profession sometimes refers to the biceps bulge symptomatic of a tendon rupture as the "Popeye muscle."[13][14] Note, however, that under normal, non-spinach-influenced conditions, Popeye only has pronounced muscles of the forearm, not of the biceps.

At the end of his song "Kansas City Star," Roger Miller's character of a local TV kids show announcer says, "Stay tuned, we'll have a Popeye cartoon in just a minute."

The 1988 Disney film Who Framed Roger Rabbit featured many classic cartoon characters, and the absence of Popeye was noted by some critics. Popeye (along with Bluto and Olive Oyl) actually had a role planned for the film, however, since the Popeye cartoons were based on a comic series, Disney found they had to pay licensing fees to both King Features Syndicate and MGM/UA. MGM/UA's pre-1986 library (which included Popeye) was being purchased by Turner Entertainment at the time, which created legal complications; thus, the rights could not be obtained and Popeye's cameo was dropped from the film.[15]

Most prominently, Popeye has been associated with the vegetable spinach, and is credited by many with popularizing the vegetable among children.

In 1973, Cary Bates created Captain Strong, a takeoff of Popeye, for DC Comics, as a way of having two cultural icons – Superman and (a proxy of) Popeye – meet.

Spinach[]

The popularity of Popeye helped boost spinach sales. Consumption of the leafy vegetable increased 33 percent in the United States between 1931 and 1936 as Popeye gained popularity. Using Popeye as a role model for healthier eating may work; a 2010 study revealed that children increased their vegetable consumption after watching Popeye cartoons.[16] The spinach-growing community of Crystal City, Texas, erected a statue of the character in recognition of Popeye's positive effects on the spinach industry. There is another Popeye statue in Segar's hometown, Chester, Illinois, and statues in Springdale, Arkansas and Alma, Arkansas (which claims to be "The Spinach Capital of the World,") at canning plants of Allen Canning, which markets Popeye-branded canned spinach. In addition to Allen's Popeye spinach, Popeye Fresh Foods markets bagged, fresh spinach with Popeye characters on the package. In 2006, when spinach contaminated with E. coli was accidentally sold to the public, many editorial cartoonists lampooned the affair by featuring Popeye in their cartoons.[17]

A frequently circulated story claims that Fleischer's choice of spinach to give Popeye strength was based on faulty calculations of its iron content. In the story, a scientist misplaced a decimal point in an 1870 measurement of spinach's iron content, leading to an iron value ten times higher than it should have been. This faulty measurement was not noticed until the 1930s.[18][19][20] While this story has gone through longstanding circulation, recent study has shown that this is a myth, and it was chosen for its vitamin A content alone.

Word coinages[]

The strip is also responsible for popularizing, although not inventing, the word "goon" (meaning a thug or lackey); Goons in Popeye stories were large humanoids with indistinctly drawn faces that were particularly known for being used as muscle and slave labor by Popeye's nemesis, the Sea Hag. One particular goon, the aforementioned female named Alice, was an occasional recurring character in the animated shorts, but she was usually a fairly nice character.

Eugene the Jeep was introduced in the comic strip on March 13, 1936. Two years later the term "jeep wagons" was in use, later shortened to simply "jeep", with widespread World War II usage, and then trademarked by Willys-Overland as "Jeep".[21] Some dispute this claim, however, as the WWII jeep was designated a "general purpose vehicle," with "GP" or "GPV" aka "jeep" appearing on the paperwork.

Events and honors[]

The Popeye Picnic is held every year in Chester, Illinois on the weekend after Labor Day. Popeye fans attend from across the globe, including a visit by a film crew from South Korea in 2004. The one-eyed sailor's hometown strives to entertain devotees of all ages.[22]

In honor of Popeye’s 75th anniversary, the Empire State Building illuminated its notable tower lights green the weekend of January 16–18, 2004 as a tribute to the icon’s love of spinach. This special lighting marked the only time the Empire State Building ever celebrated the anniversary/birthday of a comic strip character.

Reprints[]

- Popeye the Sailor, Nostalgia Press, 1971, reprints three daily stories from 1936.

- Thimble Theatre, Hyperion Press, 1977, ISBN 0-88355-663-4, reprints daily from September 10, 1928 missing 11 dailies which are included in the Fantagraphics reprints.

- Popeye, the First Fifty Years by Bud Sagendorf, Workman Publishing, 1979 ISBN 0-89480-066-3, the only Popeye reprint in full color.

- The Complete E. C. Segar Popeye, Fantagraphics, 1980s, reprints all Segar Sundays featuring Popeye in 4 volumes, all Segar dailies featuring Popeye in 7 volumes, missing 4 dailies which are included in the Hyperion reprint, November 20–22, 1928, August 22, 1929.

- Popeye. The 60th Anniversary Collection, Hawk Books Limited, 1989, ISBN 0-948248-86-6 featuring reprints of a selection of strips and stories from the first newspaper strip 1929 onwards, along with articles on Popeye in comics, books, collectibles, etc.

- E. C. Segar's Popeye, Fantagraphic Books, 2000s, reprints all Segar Sundays (in color) and dailies featuring Popeye in 6 hardcover volumes.

- Vol. 1: I Yam What I Yam – covers 1928–30 (November 22, 2006, ISBN 978-1560977797)

- Vol. 2: Well Blow Me Down! – covers 1930–32 (December 19, 2007, ISBN 978-1560978749)

- Vol. 3: Let's You and Him Fight! – covers 1932–33 (November 15, 2008, ISBN 978-1560979623)

- Vol. 4: Plunder Island – covers 1933–35 (December 22, 2009, ISBN 978-1606991695)

- Vol. 5: Wha's a Jeep – covers 1935-37 (March 21, 2011, ISBN 978-1606994047)

- Vol. 6: Me Li'l Swee'Pea – covers 1937-38 (November 15, 2011, ISBN 978-1606994832)

Thimble Theatre/Popeye characters[]

- Main article: Full character list

Characters originating in the comic strips[]

Popeye with Pipeye, Peepeye, Poopeye and Pupeye in Famous Studios' Me Musical Nephews (1942)

Listed in order of original appearance

- Olive Oyl

- Castor Oyl (Olive Oyl's brother)

- Cole Oyl (Olive Oyl's father)

- Nana Oyl (Olive Oyl's mother)

- Ham Gravy (full name Harold Hamgravy, Olive Oyl's original boyfriend)

- Popeye the Sailor

- The Sea Hag

- The Sea Hag's vultures, specifically, Bernard

- J. Wellington Wimpy

- George W. Geezil (the local cobbler who hates Wimpy)

- Rough House (a cook who runs a local restaurant, The Rough House Cafe)

- Swee'Pea (Popeye's adopted baby son in the comics, Olive's cousin in the cartoons)

- King Blozo

- Toar (a 900 pound caveman living in the modern age)

- Bluto/Brutus

- Goons, specifically Alice the Goon

- Poopdeck Pappy (Popeye's 99-year-old long-lost father; also a sailor)

- Eugene the Jeep

- Barnacle Bill (a fellow sailor and old friend)

- Oscar

- Dufus (the son of a family friend)

- Granny (Popeye's grandmother and Poopdeck's mother)

- Bernice (Known as the "Whiffle Bird" in 1960s TV episodes)

- O. G. Watasnozzle (a character with a large nose, as his name indicates)

- Otis O. Otis, "The world's smartest detective" as well as Wimpy's cousin filmmaker Otis Von Lens Cover

Characters originating in the cartoons[]

- Pipeye, Pupeye, Poopeye and Peepeye (Popeye's identical nephews)

- Shorty (Popeye's shipmate in three World War II era Famous studios shorts)

- Deezil Oyl (Olive's niece, a conceited brat who appears in three of the 1960s episodes)

- Popeye Junior (son of Popeye and Olive Oyl, exclusive of the series Popeye and Son)

Filmography[]

Theatrical and Television cartoons[]

- Popeye the Sailor (produced by Fleischer Studios) (1933–1942, 108 cartoons)

- Popeye the Sailor (produced by Famous Studios) (1942–1957, 122 cartoons)

- Popeye the Sailor (1960–1962; produced by Jack Kinney Productions, Rembrandt Films (animated by Gene Deitch), Halas and Batchelor, Larry Harmon Pictures, TV Spots, and Paramount Cartoon Studios for King Features Syndicate, 220 cartoons)

- The All-New Popeye Hour, later The Popeye and Olive Comedy Show (1978–1983, CBS; produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, 159 cartoons)

- Popeye and Son (1987–1988, CBS; produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, 26 cartoons)

- The Popeye Show (2001–2003, Cartoon Network, repeats)

In total, 638 Popeye cartoons were produced between 1933 and 1988.

Television specials and feature-length films[]

- Popeye Meets the Man Who Hated Laughter (1972)

- The Popeye Valentine's Day Special: Sweethearts at Sea (1979, produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions)

- Popeye (1980 live-action film, produced by Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Pictures, directed by Robert Altman)

- Popeye's Voyage: The Quest for Pappy (2004 telefilm, produced by Mainframe Entertainment for Lions Gate Entertainment and King Features)

DVD collections[]

- Popeye the Sailor: 1933-1938, Volume 1 (released July 31, 2007) features Fleischer cartoons released from 1933 through early 1938 and contains the color Popeye specials Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor and Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba's Forty Thieves.

- Popeye the Sailor: 1938-1940, Volume 2 (released June 17, 2008) features Fleischer cartoons released from mid-1938 through 1940 and includes the last color Popeye special Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp.

- Popeye the Sailor: 1941-1943, Volume 3 (released November 4, 2008) features the remaining black-and-white Popeye cartoons released from 1941 to 1943, including the final Fleischer-produced and earliest Famous-produced entries in the series.

- Popeye - 75th Anniversary Collector's Edition (released April 27, 2004) features 85 cartoons from the Popeye the Sailor 1960s series.

- Popeye and Friends: Volume 1 (released June 17, 2008) features a collection of eight cartoons from The All-New Popeye Hour. A second volume containing cartoons from Popeye and Son was scheduled, but it was cancelled before being released.

Sources[]

- ↑ "Review: Popeye #1", Geeks of Doom, April 25, 2012

- ↑ Popeye From Strip To Screen

- ↑ CD liner notes: Saturday Morning: Cartoons' Greatest Hits, 1995 MCA Records

- ↑ "A Clean Shaven Man", July 2010.

- ↑ 1930s Popeye the Sailor Wheatena audio clip.

- ↑ Sony making a CG Popeye Film

- ↑ Sony Pictures Animation and Arad Productions Set Jay Scherick & David Ronn to Write Animated POPEYE

- ↑ Popeyes in Puerto Rico | Cartoon Brew

- ↑ Club mascots (in Portuguese). Flamengo official website. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ↑ Grandinetti, p. 4.

- ↑ Popeye: The First Fifty Years. New York: Workman Publishing. Pages 44–45.

- ↑ Blackbeard, Bill, "The First (arf, arf!) Superhero of Them All". In Dick Lupoff & Don Thompson, ed., All In Color For A Dime Arlington House, 1970.

- ↑ Management of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tears – February 15, 1998 – American Family Physician

- ↑ Guideline not published

- ↑ Who Framed Roger Rabbit - Trailer - Cast - Showtimes - NYTimes.com

- ↑ Toronto Globe and Mail, "How to win the kids v. veggies battle", Aug. 16, 2010

- ↑ No Eats Me Spinach!

- ↑ Hamblin, T.J.(1981) Fake! British Medical Journal Vol. 283.19–26 December. pp.1671-1674

- ↑ E.C. Segar, Popeye's creator, celebrated with a Google doodle

- ↑ The 7 Most Disastrous Typos Of All Time

- ↑ Word Origins.

- ↑ Chester, Illinois Official Website